Tender Objects: Emotion and Sensation after Minimalism

Exhibition Guide

Sticky Objects

Allusion and Illusion

Unfolding Time

Sticky Objects

Minimal artists often sought to activate viewers’ awareness of their own bodies through a provocation of an object’s palpable characteristics. While reduced in their forms, the evocative tactility of these objects works to trigger the senses, and is what ultimately “sticks” or sustains when engaging with and responding to them.

Janine Antoni

American, born Bahamas 1964

Lick and Lather, 1993

One licked chocolate self-portrait bust and one washed soap self-portrait bust on pedestals

Edition of 7 plus 2 Artist Proofs and Test Proof

The Rachofsky Collection

Describing her practice, Janine Antoni has stated that “all of my objects sort of walk the line between sculpture, performance, and relic.”[1] In Lick and Lather, Antoni evokes classical portraiture through busts cast in familiar materials — chocolate and soap — thereby subverting expectations of materiality and self-representation. The complete series of fourteen total busts, seven of each material, cleverly references the Greek aesthetic ideal height of seven heads. Antoni sculpts not with a chisel but her own body, giving the chocolate bust a bronze-like patina through licking and recreating the appearance of marble by lathering the soap bust. She characterized the veritable consumption of herself as “really frightening” but described the latter act as “the most beautiful process in the world — like washing a baby.”[2] The purposefully disfigured busts thus stand as imprinted remnants of the bodily actions enacted through their creation.

[1] “Janine Antoni Lick and Lather, 1993,” Art Object Page, National Gallery of Art (accessed November 30, 2020) https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.206257.html#overview

[2] Kay Larson, “Women’s Work (or Is It Art?) Is Never Done,” New York Times (January 7, 1996) https://www.nytimes.com/1996/01/07/arts/art-women-s-work-or-is-it-art-is-never-done.html

Janine Antoni

American, born Bahamas 1964

Umbilical, 2000

Sterling silver cast of family; silverware and negative impression of artist’s mouth and mother’s hand

Collection of Deedie Rose

Metaphors of infancy and motherhood are once again evoked in Janine Antoni’s Umbilical, where the artist conjures memories of her childhood by employing the family’s silverware. The idea of nourishment, intimately connecting mother and child, is not only suggested in the work’s title but also elicited through the piece’s materiality and creation process — traces of the inside of the artist’s mouth were imprinted on the bowl of the spoon, while the inside of her mother’s hand was cast on the handle. As in Lick and Lather, Umbilical also reveals the artist’s customary interdisciplinary approach combining three-dimensional objects and performance, emphasizing the artist’s bodily actions, and calling attention to the making process.

Tom Friedman

American, born 1965

Untitled, 1990

Bubblegum

The Rachofsky Collection

Tom Friedman transforms everyday objects, pushing the capacities of mundane substances, like toothpaste and toothpicks, pencils, and soap. Friedman’s meditations on the nature of disposable things — their commonplace identities, purposes, and functions — have the ability to extract and reveal an unacknowledged essence, changing the way the viewer may see what they take for granted. Base substances are transformed through multiplication, amplification, and polish — laborious and meticulous efforts that achieve spectacular and unrecognizable forms.

Friedman chewed 1,500 pieces of pink bubblegum to make Untitled. Thus, the smooth surface of the orb conceals the imprint of its creator as well as its mundane materiality. Friedman places shape, color, concept, and display at the forefront of his work. While the volume of the monochromatic sphere engages Minimalist ideals, its diminutive form, trivial material, and corner placement — as though stuck to the wall by its own viscosity — teases traditional notions of neutral, serious art. In contrast to the uncanny and unsettling transformations usual in art, Friedman’s works veer toward the whimsical and even the sublime.

Victor Grippo

Argentinian, 1936–2002

Vida, Muerte, Resurrección (Life, Death, Resurrection), 1980

Five hollow geometrical lead bodies; five hollow geometrical lead bodies filled with black and red beans; water; glass box

Collection of Deedie Rose

Systems and material processes are central to Victor Grippo’s investigations, developed from his previous training in chemistry. His installations and sculptural works translate the symbolic into real world situations, incorporating natural progression and material transformation. Like an alchemist, fusing art and science, Grippo’s work operates through transforming matter into energy. This can be observed in the piece on display, Vida, Muerte, Resurrección (Life, Death, Resurrection), where beans soaked in water expand, rupturing the lead-made geometric structures. This process reveals that even small humble actors like beans can generate force to alter larger structures. This emphasis on change resulting from natural processes can also be read as a response to the political struggle during the repressive years of Latin American military dictatorships.

A conceptualist artist, his work often operates at a linguistic level through analogy; bread, maize, and potatoes invoke alimentation, a fundamental need to human life; tools and materials conjure labor; associations with liberation and hope can be made through beans bursting the lead surfaces of containers and germinating.

Fernanda Gomes

Brazilian, born 1960

Untitled, 2010

Walnut, needle, and linen thread

The Rachofsky Collection

Fernanda Gomes deploys mundane, often useless and disposable materials and objects from everyday life − which she calls “things.” The use of commonplace items suggests associations with the artist’s personal routine while their ordinariness drains them of any sentimentality. Gomes’ working process revolves around rearranging things in relation to one another and to the environment, removed from a utilitarian logic. Although her method implies uncomplicated actions like tying, nailing, and hanging — that can be observed in the piece on display — it emerges from a complex thought process developed through an extended focused time in the studio. According to Gomes, this practice allows her to “search for a certain awareness of being somewhere while enlarging this perception.”

In Untitled, Gomes employs an economy of elements based on the minimum necessary to construct a simple structure — a vertical line against a flat plane, with two foci of tension at both ends, the walnut and the nail. This structure of opposites generates further tense, unresolved associations that are pervasive in Gomes’s artistic investigations: the conflict between suggestion of movement and resting state, precariousness and endurance, obsolescence, and suspension in time.

Allusion and Illusion

In possessing an acute awareness of materiality — especially an object’s inherent and perceived functions — these artists transform, reconstruct, and defy the physical characteristics of substances in their work, thereby destabilizing a medium’s expectations and offering new possibilities in meaning.

Mona Hatoum

British Palestinian, born Beirut 1952

Nature morte aux grenades, 2006–07

Crystal, mild steel, and rubber

The Rachofsky Collection and the Dallas Museum of Art through the TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund

Mona Hatoum’s Nature morte aux grenades exemplifies the opaque motives of an oeuvre which defies neat categorization, despite references to Surrealism, Minimalism and consistent themes of displacement, war trauma, and corporeality. Here, form complicates language. Beautifully blown-glass spheres invite impressions of decorative fruit objets d’art, implied by a translation of the title which might read Still Life with Pomegranates that could reference a painting of the same title by Henri Matisse. Closer inspection, however, reveals meticulously shaped weapons of war. The grenades are further complicated by the steel medical cart on which they rest, whose handles hint at pushing the body suggested by its surface. The potential energy evoked by the wheels emphasizes the fragility of the Murano glassworks and the inherent destructiveness of the forms they represent, thus destabilizing the work’s static appearance and unfixing a conclusive interpretation.

Seung-taek Lee

Korean, born 1932

Paper Tree, 1970s

Korean mulberry paper and tree branch

The Rachofsky Collection

Seung-taek Lee’s work is inherently grounded in the post-Korean War avant-garde. Korean art of the period was understood to embody either a presumably archaic style of the East or the modern, yet foreign, trends of the West. In contrast, critics heralded Lee as an “outsider” to everything except Korean influences, which informed his work through layers of symbolism, history, and materiality. Paper Tree manifests Lee’s argument, noted by Kyung An, that his Wind series, of which it is a part, constituted “some of the first works to modernize Korean tradition and culture.”[1]

Paper Tree simultaneously conjures the decorative fabric strips of guardian trees in village shrines, seonangdangs, and the historically symbolic importance of paper. Past and present are bound together through the union of paper and branches, bearing traces of what once was and what remains. Its branches float effortlessly even as thin paper strips weigh them down, thus suspending Paper Tree in time and space. Invoking the senses, Paper Tree invites the viewer to imagine the sound of the infinitesimal rustling of the paper swaying in the breeze. Lee’s work communicates to diverse audiences, as he stated, “I take inspiration from Korean heritage, because things that are the most ethnically specific and local are also the most international.”[2]

[1] Kyung An. “Between the Local and the Global: Seung-Taek Lee in the 1960s and 1970s.” In Seung-Taek Lee, edited by Lévy Gorvy, 11–15. (New York: Artbook, 2017).

[2] Ashley Rawlings, “Lee Seung-Taek: Harnessing the Elements,” ArtAsiaPacific (July/August 2010).

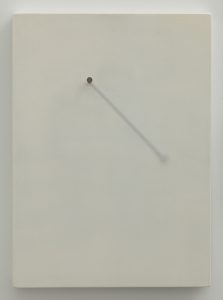

Jiro Takamatsu

Japanese, 1936-1998

Shadow of a Nail No. 400, 1975

Lacquer and iron nail on wood panel

The Rachofsky Collection

Jiro Takamatsu — a foundational figure of both the Hi-Red Center collective and the Mono-ha (School of Things) movement — captures transient and generally mundane moments, freezing the fleeting details inscribed by shadow like in Shadow of a Nail No. 400. Takamatsu’s painted shadows, a series that flourished in the 1960s but extended through the remainder of his career, often describe passing gestures cast against a wall — the fragments of torsos and limbs in motion. Such silhouettes represent the removal of the body which has uncannily left the shadow that should have followed. Other silhouettes focus on the traces of negligible details permanently affixed to the wall, hooks and hangers and nails. Although such hardware may be stable, their shadows emerge, alter, and dissolve, depending on transitory sources of light. The direction of the shadow and the softness of its gray compels the viewer to consider the location of the represented light source, creating a conceptual field in which the viewer also stands. Takamatsu’s spare forms thus open space as they freeze time.

Sheila Hicks

American, born 1934

Hieroglyph Wuppertal, 1966

Linen

Collection of Deedie Rose

Sheila Hicks always highlighted her indebtedness to South American and Mexican weaving cultures throughout her career, making clear that what has always drawn her to Andean textiles was not “the compositions or the iconography…[but] their vocabulary, their way of moving lines in space and threads.”[1]This geographical metaphor invoked by the idea of “moving lines in the space” not only manifests in the artist’s making process but also speaks to Hicks’s trajectory, moving across continents intertwining different textile traditions.

Hicks studied painting at Yale (1954-1957), where she had advisors who helped her to develop her practice. George Kubler introduced her to pre-Columbian art and the notion of deep time connecting present and ancient art forms, also fundamental to Land Art artists. Leading Bauhaus artist Josef Albers sparked modernist concerns, that can be observed in Hieroglyph Wuppertal. Through Josef Albers, she met weaver-artist Anni Albers who guided her through the structural principles of the practice.[2] This piece presents surface oscillations that disturb the canonical flatness and neutrality of modernism’s championed form, the monochrome. Her Bauhaus-informed hybrid of art, design, fashion, and architecture challenges the principle of medium autonomy.

[1] Cavanagh, Alice. “Inside Textile Artist Sheila Hicks’s Paris Studio; For Six Decades, Artist Sheila Hicks Has Been Pushing the Boundaries of Her Chosen Medium, Fiber, and in the Process, Challenging Conceptions of Art More Broadly. WSJ. Goes Inside Her 6th Arrondissement Studio in Paris to See Several Works in Progress.” The Wall Street Journal. Eastern Edition (2019).

[2] “My encounters with Anni Albers,” Tate Etc. (accessed Jan 12, 2022) https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-44-autumn-2018/anni-albers-sheila-hicks

Unfolding Time

Even the simplest objects may provoke a deeply felt sensation of the transience of moments we experience, of our place in the flow of time. The shifting nature of form and hue may stimulate anticipation, the expectation of change — while a date, a color, an everyday object can summon the atmosphere of a place we once lived, a feeling of who we once were.

Anne Truitt

American, 1921–2004

Valley Forge, 1963

Acrylic on wood

The Rachofsky Collection

Anne Truitt merges painting with sculpture, embodying color in objects scaled to the viewer and positioned to invite engagement. In Daybook, the first of her published journals, Truitt wrote that her aim was to, “take paintings off the wall, to set color free in three dimensions for its own sake.”[1] Valley Forge compels contemplation by means of subtle and nuanced tensions in form and color. Two shades of red suggest the vibration of close harmony, interlocking and wrapping around the piece to suggest a volumetric form which contradicts the physical construction of three adjacent sections. Although the sculpture’s title refers to historic events, Truitt also drew upon recollections of her time in college at nearby Bryn Mawr. While such intimate details from Truitt’s own life are inaccessible to the public, she refracts her own personal memories through the allusive and fundamentally subjective capacities of color, form, and structure to evoke instead similar sensations which viewers may draw from their own experiences.

[1] Anne Truitt, Daybook: The Journal of an Artist (New York: Pantheon Books, 1982).

On Kawara

Japanese, 1933–2014

May 25, 1966, 1966

From the Today series

Acrylic on canvas

The Rachofsky Collection, an anonymous collection, and the Dallas Museum of Art through the TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund

On Kawara

Japanese, 1933–2014

6.AUG.1976, 1976

From the Today series

Acrylic on canvas

The Rachofsky Collection, an anonymous collection, and the Dallas Museum of Art through the TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund

On Kawara

Japanese, 1933–2014

10 JUL.1986, 1986

From the Today series

Acrylic on canvas

The Rachofsky Collection, an anonymous collection, and the Dallas Museum of Art through the TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund

On Kawara was acutely concerned with how time could be experienced and documented. Exemplary of this fixation is Kawara’s Today series, which was begun on January 4, 1966, and continued until Kawara’s death, resulting in nearly 3,000 canvases. As the series’ title suggests, Kawara sought to create paintings depicting each day’s date. He established strict rules for the project, such as formatting the date in the language of his location, destroying the painting if it was not completed before midnight, mixing the pigments himself, and hand-painting the script without stencils — resulting in slight discrepancies throughout the series, unveiling Kawara’s hand.

Kawara developed an archival system for the series that included boxes lined with the day’s local newspaper and journals filled with the paintings’ information, including their subtitles. Subtitles in the 1960s fluctuated between violent newspaper headlines and personal anecdotes, while the majority of later subtitles merely recorded the day of the week. The subtitle for May 25, 1966 reads, “A rocket scientist was killed by a foreign-made .25 caliber pistol, Columbus Ohio,” while 6.AUG.1976 is “Freitag” (Friday in German) and 10 JUL.1986 is “Jaudo” (Thursday in Esperanto, which Kawara used for languages outside the Latin alphabet). While ostensibly objective in its execution, the recordkeeping in Kawara’s Today series subtly reveals both the individual and universal experience of existing in time.

Nobuo Sekine

Japanese, 1942–2019

Phase No. 10, 1968

Wood, oil-based paint, and FRP

The Rachofsky Collection and the Dallas Museum of Art through the TWO x TWO for AIDs and Art Fund

Central to Nobuo Sekine’s methodology was the study of topology — the mathematical concept concerned with transformation in geometry and space. Created the same year as the career-defining Phase—Mother Earth (also in The Rachofsky Collection), Sekine sought to explore the malleability of three-dimensional forms in his Phase works. For Sekine, the term phase (isō in Japanese) referred to the idea of a continuous passage between different states of being, particularly of space and time. These series of works, particularly, Phase—Mother Earth, would ultimately influence the formation of the Mono-ha (School of Things) movement in Japan which rejected conventional ideas of representation and concentrated on engaging with the properties and elements of materials.

In Phase No. 10, Sekine inverts a cylinder’s shape, making the solid surface of the wood pliable and, with the elliptical gradation of fluorescent green to yellow, directs the eye through a continuous loop that distorts the shape’s inside from out. The trompe l’œil, tricking of the eye, invoked in Phase No. 10 manifests Sekine’s pursuit to develop a “new awareness and interpretation in space,” by not exhibiting the cylinder’s fixed circuit, but exposing its boundless essence. [1]

[1] Mika Yoshitake, “PIONEERS Mika Yoshitake looks back at the art of NOBUO SEKINE,” Kaleidoscope Asia, 2 (Fall/Winter 2015) http://www.nobuosekine.com/wp-content/uploads/REGULARS_NOBUO-SEKINE.pdf

Michelle Stuart

American, born 1933

#7 Saugerties, circa 1972–73

Graphite on muslin mounted paper

The Rachofsky Collection

Like other artists exhibited in Tender Objects, such as Sheila Hicks and On Kawara, Michelle Stuart’s artistic practice involves travel and displacement across geographical distances. But in her case, spatial reference translates into the works through its materials and textures. #7 Saugerties, an early work, captures topographic patterns of the earth through a graphite rubbing technique made on the ground in Saugerties, New York.

In the 1970s, Stuart emerged as an influential post-minimal artist, most notably through her technique of smashing, pulverizing, and rubbing samples of soil and rock collected from different places to create monochromes on large paper scrolls. While her intimate and physical connections to landscape challenge the monumental scale of early Land Art, her technique and choice of materials subvert minimalist ideals of the neutrality of monochrome painting. Stuart collects fragments — raw materials and personal memorabilia — as a way to recollect intimate experiences. Personal narratives emerge in the combination and arranging of elements in her work, guided by topographic notions, childhood memories, and her own photographs. This material, selected and accumulated over time, is then amalgamated in the pieces — paintings, drawings, and objects.

Ana Mendieta

American, born Cuba. 1948–1985

Untitled (Leaf Drawing), 1984

Mixed media on leaf

Collection of Deedie Rose

Ana Mendieta’s Untitled (Leaf Drawing) derives from the Silueta series produced from 1973 through 1980, where the artist inscribed her naked body’s contours into the natural landscape. Regarded as her signature visual vocabulary, the successive repetition of her naked silhouette throughout her work not only ensures its unity and structural integrity but also adds a temporal dimension implying ideas of process, memory, and transience.

Mendieta’s artistic practice combines performative ritual and sculptural approach, producing ephemeral objects that contain vestiges of the artist’s body and references to Cuban culture, the artist’s homeland. Her work could thus be regarded as a precursor for Janine Antoni, whose work is also part of this exhibition. Mendieta’s inter-disciplinary approach — between land art, conceptual art, and performance — not only stemmed from her training with Hans Breder at the University of Iowa in the 1970s but also connected her to broader feminist postmodern practices that included discussions of gender and identity, as Mendieta herself was a female Cuban-born artist working in the United States.